A mystery depends on plot.

Yes, characters are important, even critical. The technical details behind the crime are important. The locale is often essential to understanding the story. But plot is king.

I am not a great plotter. Sure, I am very creative when it comes to coming up with strange, off-the-wall ideas. But when it comes to actually creating a tightly integrated plot, I need help. That’s when I turn to Blake-Snyder’s Save the Cat paradigm.

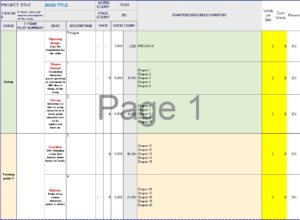

I’ve modified the Blake-Snyder form to be particularly useful to me in structuring my mystery stories. Here is the form that I use (it’s in four parts):

Seven Point Plot Summary

The Blake-Snyder Save the Cat approach starts with a seven-point structure to the plot:

- Setup

- Turning point

- Act II, Part one

- Midpoint

- Act II, Part two

- Turning point (Start of Act III)

- Act III

Many writers are entirely comfortable just using the 7-point plot outline to structure their stories. My editor, Tara Maya, uses this outline almost constantly. Her structure for fantasy and sci fi stories consists of the following word counts:

- 10,000

- 20,000

- 20,000

- 10,000

- 20,000

- 10,000

- 20,000

My cozy mystery novels are usually shorter, averaging 75,000 words. I prefer to use a lot more granular outlining structure for my stories. To accomplish this, I use the fifteen beat structure of the Save-the-Cat outline. Each of my beats usually consists of five scenes of 1,000 words each, which yields my desired word count of 75,000 words.

Some writers might find this too mechanistic and constraining. I find advantage in the fact that the shorter scene structure allows me to maintain a faster pace in my stories. With about 70 scenes in my story, I can introduce all of my potential suspects, intertwining sub-plots, and character development into a satisfying story.

The Fifteen Beat Plot Summary

I find the fifteen beat structure to be ideal for my stories. I write scenes of approximately 1000-1100 words each. The first beat and the last beat consist of one scene each. The other thirteen beats each have five scenes in them, bringing my total word count to 75,000 words.

Many writers object to such a stringent adherence to word counts. For my stories, I want consistency and predictability. My readers get lost in the mystery, not the novel itself. I am not writing an epic. I am writing escapist literature, where my audience can try to solve a crime before MacFarland does. For me, structure is critical, both as a roadmap for the reader, and a way to ensure the pace of the story corresponds with solving the mystery.

Other writers might find a different approach is more satisfying and yields a better product. The beauty of the Save-the-Cat paradigm is that it lends itself to a huge variety of stylistic ways of authoring a novel. Feel free to adopt it as you see fit.

Setup (3 beats)

The setup consists of three beats:

Opening Image – In the opening image (the Prologue), I lay the foundation for the crime. I try not to reveal who the killer is, but I want the reader to know what’s at stake.

Theme Stated – In the second beat, theme stated, I use five scenes to have a secondary character pose a question or statement to MC that is theme of the story. This section might also have threads of an over-arching plot (part of the trilogy I have in every group of three novels), as well as issues surrounding my protagonist’s life.

Set-up – In the third beat, I use five scenes to introduce or hint at every character in the “A story.” If possible, I will plant character tics to be addressed later on.

Turning point 1 (2 beats)

The first turning point in the story is the transition from introduction to action. Something has to prompt the hero, MacFarland, to take the case, get involved, or feel that he alone can handle the case.

Catalyst – The fourth beat is a life-changing event that knocks down the hero’s house of cards. In these five scenes, MacFarland finds that he cannot continue as he was, but must move along a path that brings him into the conflict.

Debate – The fifth beat is debate. The hero addresses all the pros and cons of getting involved, usually with other people of course. But it’s never a simple discussion of “should I do this?” but a series of events that make it impossible for the walk away without losing his integrity or sense of being. The hero approaches a point of no return and makes a choice that moves the story forward.

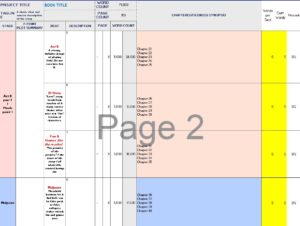

Act II Part 1/Pinch point 1 (3 beats)

Act II – The first beat of the Second Act is Act II, which usually contains a pinch point, or some event that moves the story forward in a definite manner. There is a strong, definite change of playing field. Blake and Snyder suggest that the writer should not ease into Act II, but jump in with alacrity and enthusiasm.

The second beat of Act II is the B-Story or “Love” story. The love story is often a break from tension of the primary or A story. The theme does continue, but often uses new and interesting characters to move the plot along. This beat and the following beat are two of my favorite beats in the Save-the-Cat outline. I use them to move MacFarland’s and Pierson’s on-again, off-again love affair (it’s never very pronounced, but usually hinted at).

The third beat of Act II is the Fun & Games beat. The fun and games are aimed at the reader (and therefore may not be fun and games for the story’s characters. I like to introduce humor into these two scenes, usually more humor than in the rest of the novel. Consequently, I usually spend a lot more time working on these scenes, since, to be quite honest, mine is not the most humorous or comedic personality on the bookshelf.

Midpoint (1 beat)

The Midpoint has only one beat. It is the doorway between the first half of the story and the second half. The midpoint can be false peak or false collapse, bur regardless, the stakes are raised. The time for fun and games is over.

It the midpoint is a false peak, it usually consists of MacFarland coming to an erroneous conclusion about who the murderer is. The reader knows his conclusion is wrong (after all, there is still half of the book to go!), but the reader has to perceive the error of MacFarland’s thinking. If the midpoint is a false collapse, the reader must see that there is a way out of the mess, if only MacFarland was as smart as the reader.

Act II Part 2/Pinch point 2 (3 beats)

This is the part of the story that the reader has been waiting for. Everything goes wrong, MacFarland is in trouble, his solution to the case is proven wrong or disastrous, and the villain is about to change the outcome of the story.

There are three beats in Act II Part 2

Beat number ten, Bad Guys Close In, is the beat in which the villain “formally” acknowledges that MacFarland is his main threat and he regroups. He may send in henchmen and others who will disrupt MacFarland and his team. While MacFarland may not waver, his team begins to unravel and fall apart.

The eleventh beat is All is Lost. This is the opposite of midpoint, where a false victory or even a false defeat is shown to be what it is. The main characters must change how they view the situation they find themselves in or face defeat. The more I can show that things are going bad for MacFarland, the happier I am as a writer.

And I’m sure the reader loves it as much as I.

The twelfth beat is the Black moment, the darkest point in the story. MacFarland has lost everything – he hasn’t solved the case, there’s a chance the villain is going to escape, all his suspects are proving to be false flags.

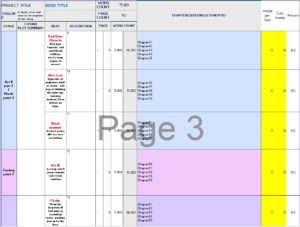

Turning point 2 (1 beat)

The thirteenth beat is the second turning point in the story, the start of Act III. Unlike a pinch point, where things get worse, a turning point is a change in direction. The main reason for Turning Point 2 is that the A story and B story combine to reveal a potential solution.

One of the things I like to do in this beat is show that MacFarland and Pierson need each other to be successful. His dominant strength, the ability to think outside the box, needs her insight and logic to keep his analysis real. Separately, they might be good; together, they are spectacular. Okay, spectacular is a bit extreme. But darned good!

Act III (2 beats)

Act III has two beats:

Finale – Wrap-up; dispatch all bad guys in ascending order, working way up to the boss.

Final Image – Opposite of opening image; show how much change has occurred (including Epilogue)

Beat 14 – Finale

The finale contains the action scenes of the mystery. MacFarland has to confront the murderer and expose him or her. Often these scenes involve rescuing someone critical to the story. And not infrequently, Detectives Pierson and Lockwood show up just in the nick of time to help MacFarland.

I don’t often have scenes in which my main character engages in fisticuffs with the villain. This is for two reasons. First, although MacFarland is a solid, well-muscled (and sexy) individual, he is not the kind of man who solves all his problems with his fists. And second, I don’t like putting MacFarland in positions where he has to kill his suspect. A dead suspect, except in rare circumstances, is not much of a solution to a mystery.

The finale often includes a scene where MacFarland explains the case to those around him. What happened, how the murderer committed the crime, and often what detail gave MacFarland insight to solving the murder. If there are too many action scenes, this final review of the case may take place in the Final Image.

Beat 15 – Final Image

The final image of the story wraps up a lot of the loose threads that have been woven into the story’s fabric. Relationships between characters are often in focus during these scenes. I may also throw out hints of future events in this section.

The Epilogue serves a special purpose in my stories. It is a bridge between the three books of the over-arching trilogy plot. It foreshadows the conflict that might come in the next book in the series.

In summary, the Blake-Snyder plot outline allows me to structure my stories so that they consistently deliver a story line that moves along both logically and, I hope, briskly. Blake-Snyder keeps me honest to the story, honest to the mystery, and able to keep producing story after story. I hope that the books in the Hot Dog Detective series remain individual enough to keep a reader interested in reading what will be a twenty-seven volume series. And I hope the mysteries are well-enough presented to keep the avid reader guessing, who did it?