his may be a bad idea, but I’m going to take the magic out of writing mysteries. I think there are simply not enough books in the world, and with more and more books being banned, we need more writers out there. So this is an attempt to teach young, old, or simply aspiring writers how I go about the task of plotting a story. To demonstrate this, I’m going to describe the steps I go through to plot a Crystal Cove Cozy Mystery.

My starting point is almost always a title and a core mystery structure. For example, I had the title “The Ghost on the Stairs” and I knew that the general plot would be a person who died or was killed on a stairway. By knowing that the person died on a stairway, I also know that the general mystery will be how did the victim really die? Was it an accident? Or was it something more nefarious?

The next step in my writing process is to focus on characters. I start with the main character, in this case Sally O’Brian, an ex-school teacher in her mid-fifties. She is married to Matthew O’Brian, an investment broker who helps start-ups get off the ground. I will develop characters to fill out their respective families, though creating these characters continues over time. I also need to know who the victim is, and develop his or her back story. This leads me to who the actual killer is. But a good mystery needs more than a killer. It needs other suspects, so I have to create those characters. By the time I finished brainstorming characters, I often have twenty to thirty characters identified for the story.

Next comes the hard part. Plotting.

My Crystal Cove mysteries consist of two parts. The first part will be the “mystery” – that is what Sally and the ghost have to solve. The second part will be a sub-plot, a mini-romance story involving a young man and a young women. They will figure prominently in the mystery plot, but they also have to fall in love by the end of the story. As a general rule, all of my romances are HEA (“Happily Ever After”) stories. No, it’s not a general rule. It’s quite absolute. I want people to find love and happiness in my stories.

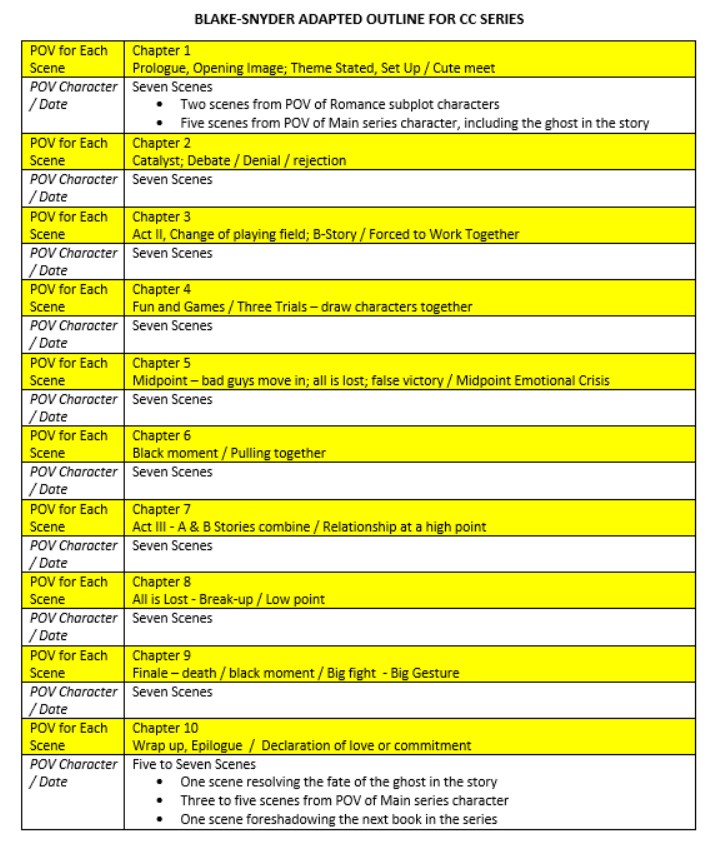

There will be ten chapters in the book, each chapter with seven scenes. I have to determine for each scene whose point of view I will have (five of the scenes will be from Sally’s point of view, and one each from my female protagonist and my male protagonist in the romantic subplot in the story. I use a variant of the Blake-Snyder Save the Cat plotting outline to structure my stories. Thus, Chapter One will have scenes that will introduce any prologue to the story, any opening images I need for the story, a statement of the theme (usually by interactions of the characters), and a set up for the remainder of the story. Chapter One will also include the “Cute meet” for the romance story – introducing my two main sub-plot characters.

I also have to accomplish the aims of the Blake-Snyder outline for that chapter in approximately 7,000 words, which is my target for each chapter. (See Figure 1.)

I cannot emphasize enough the importance of the Blake-Snyder Save the Cat outline concept. Stories are more than mere collections of words. They are more than characters and scenes. They are about solving a problem or achieving a goal. A story without a problem or a goal is a biography or a narrative. It is the problem that brings a story to life.

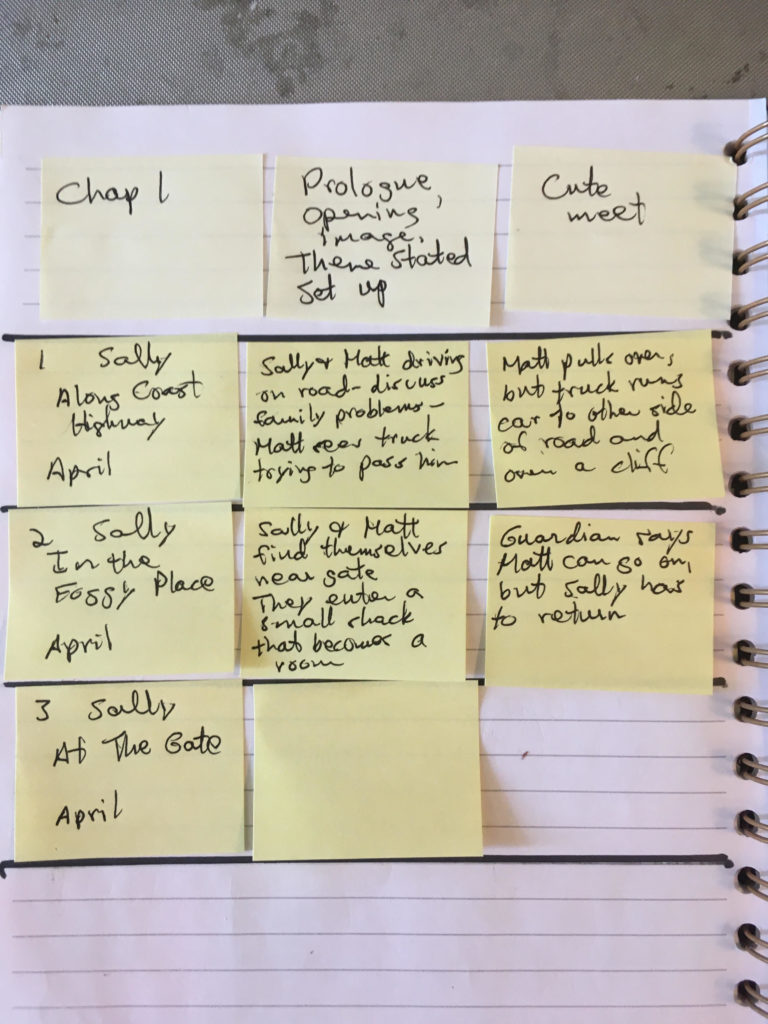

Using the Blake-Snyder outline as a guide, I then try to determine what plot actions take place in the story. Usually, for a 1,000 word scene, I need two to four plot points. I record these plot points on Post-its (which makes them easy to move around on my plotting notebook. As you might have surmised by now, even my Post-its imply a structured approach to my writing. Each Post-it should represent 250 to 400 words in the scene. (See Figure 2)

The plot point written on the Post-it is simply a prompt or reminder of what is going on in that scene. In and of itself, it is incomplete. That’s where the creative part of being a writer comes in. Every plot point needs to be developed in order to create a satisfying story.

My first Post it has the following information on it: “Sally and Matt driving on road – discuss family problems – Matt sees truck trying to pass him.” Since this is the first scene of the first book in the series, I know that I have to include a lot more information than just that plot point. The plot point becomes the skeleton on which I hang the gist of the story: Who is Sally O’Brian? What does she look like? What does she do? Who is Matt? Why are they driving on the road? What time of day is it? Where are they coming from? Where are they going? What sort of family problems are they discussing? What are their attitudes towards these problems? Do the problems affect what is currently happening to them? What is Matt’s reaction to the truck trying to pass him? What does the other driver do?

By asking all of these questions (which I hope are questions the reader would also have), I can turn 16 words into several hundred words. More importantly, I can set up a scene that will draw the reader in and get the reader interested in the next plot point…what happens next?

Writing a story is a lot of work. But if you use the tools I have described, it can become a lot easier. And hopefully, someday, I will see your books competing for readership.